Huge Antarctic ice sheet ‘melted during similar temperatures to today’ raising fears of catastrophic global floods

Flooding of huge swathes of land caused by the melting of a huge Antarctic ice sheet around 125,000 years ago, could be seen again today because the world's temperatures are similar, scientists have suggested.

Temperatures during this interglacial period, also known as the Emian, were only one or two degrees warmer than today's average temperatures across the planet, but sea levels were between six and nine metres higher.

Since then, the most recent ice age froze the earth, but although temperatures are once again on the rise, sea levels only risen modestly.

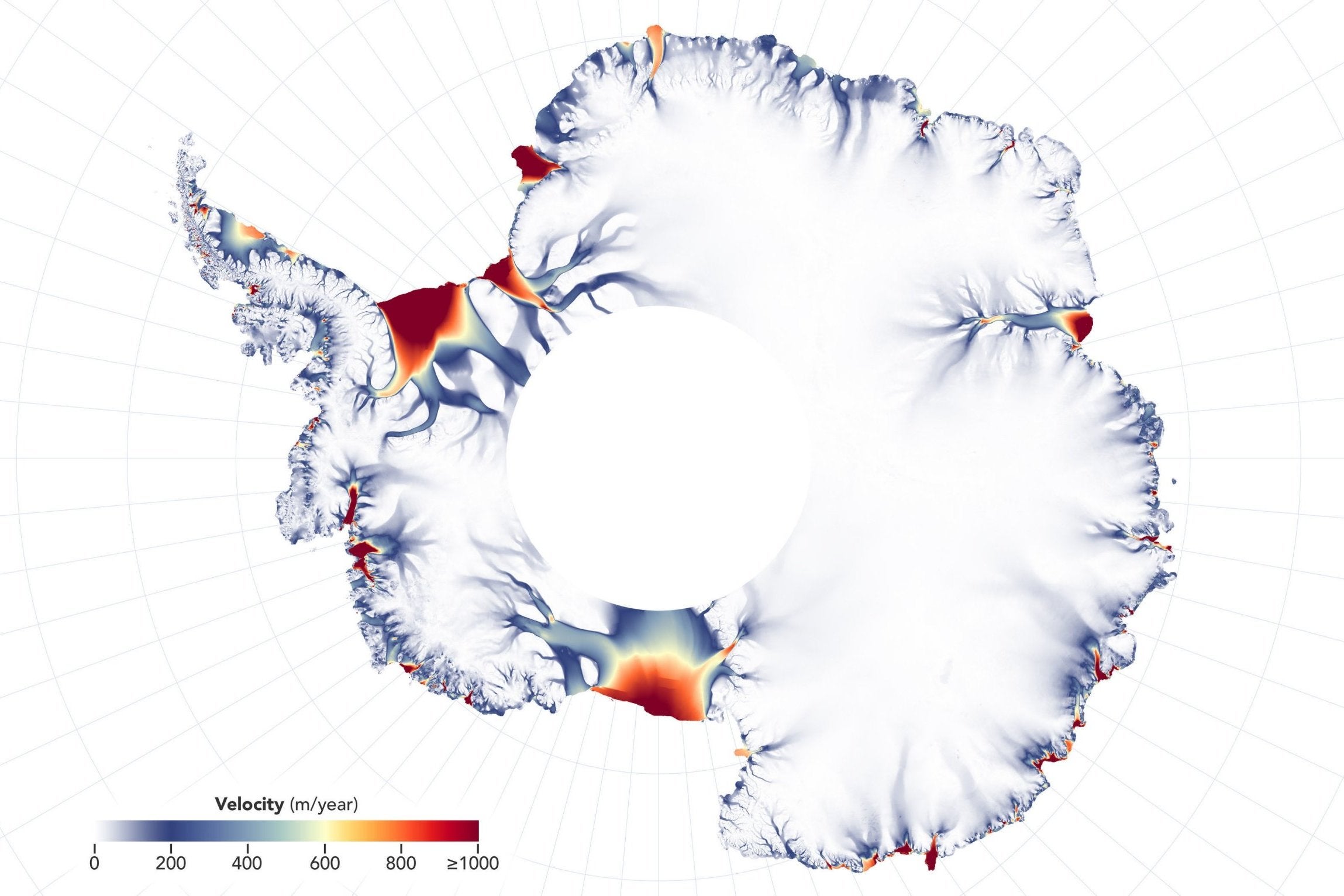

New evidence has suggested that a huge mass of water, currently locked away in the West Antarctic ice sheet, was exposed to rising temperatures during the Emian period as a result of slight changes in the Earth’s orbit and spin axis.

It is thought that the warmer climate caused the ice sheet to melt and what was dry land became subaquatic terrain.

Findings from a sediment core taken from the West Antarctic ice sheet presented at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington DC this week, provides evidence suggesting the ice sheet disappeared during a period of climate similar to ours today.

“We had an absence of evidence,” said Anders Carlson, a glacial geologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, who led the work. “I think we have evidence of absence now,” ScienceMag.org reports. “Our record thus provides the first direct indication of a much smaller last interglacial West Antarctic ice sheet,” the research paper says, adding the work provides the historic geological context for the susceptibility of the West Antarctic ice sheet to collapse again."

As we begin to understand the extent to which humans are driving climate change, glaciologists fear a collapse in the Antarctic ice sheet could again send sea levels rising, this time resulting in devastating world floods.

Until recently the collapse of the vast ice sheet covering Greenland had been blamed for the surge in sea-level rises during the Emian period.

But in 2011, a team also led by Mr Carson excluded Greenland from the investigation after isotopic records indicated during this period ice had continued to grind away at the surface of the rock.

The team then turned to the West Antarctic ice sheet. They initially studied 29 marine sediment cores to identify relevant isotopes created by erosion of rock by ice.

They then studied one core in particular, from the Bellingshausen Sea, west of the Antarctic Peninsula. This provided a 140,000-year-record of deposits from various land masses eroded by sea ice.

During the later part of the Emian period, the record from the West Antarctic ice sheet completely disappeared, indicating it had melted.

“We don’t see any sediments coming from the much larger West Antarctic ice sheet, which we’d interpret to mean that it was gone. It didn’t have that erosive power anymore,” Prof Carlson said.

Fears have been raised the Antarctic ice sheet as well as the huge glaciers locked in by the ice shelves are already irreversibly melting at a rising rate.

Earlier this year it was reported the continent has lost about 3 trillion tonnes of ice in the last 25 years.

The UK-sized Thwaites glacier in west Antarctica, is fast retreating and this volume of water alone would ultimately raise global sea level by about three metres, scientists warned in September this year.

Meanwhile, Nasa has detected new signs large glaciers in East Antarctica, previously thought to be stable are losing ice, also raising the prospect of catastrophic sea level rises as global temperatures increase.

Comments

Post a Comment